Since I was old enough to read, I wanted to be an author. There was just one problem: I could rarely ever muster the energy to actually sit down and write. My drafts seemed to progress at a snail’s pace, to the point where the comic versions of my stories were outstripping my progress on their novel counterparts. To put that into perspective, a single comic page took over 10 hours to craft and had the equivalent story progress as two or three paragraphs of prose — if that.

It was hopeless, I thought. I will never be a novelist.

Comic scripts — those were easy. I could write a chapter in one or two afternoons and then not have to touch my keyboard again for months, maybe even years, until I’d finished drawing everything I’d written. No one needed to see my scripts, so they could be sloppy and vague as I let my art do all of the heavy lifting.

Unlike my scripts, people eventually would see the words I was putting down in a novel. With that hyper-awareness of how every single sentence sounded, I found myself grinding to a halt whenever my prose sounded even slightly awkward. Did I really just write a grammatically incorrect sentence? For shame! Did I use the wrong word for that context? How abhorrent! Did I repeat the same unique word too many times? Out, damned inkblot! Out, I say! I expected every sentence to be perfect before I moved on to the next, and if it wasn’t, I would cringe, mortified by my failure to grasp my native own language. My flow state ruined, I would close my word processor and obsess over my mistakes for months until the next time a rare bout of insatiable inspiration struck.

My midlife crisis decided to blindside me while the pandemic was raging. After a miniature breakdown, I emerged with some new perspectives. I looked at my comics and how little they’d progressed in the nearly 20 years I’d been working on them. I realised if I didn’t get serious about being a novelist, I was never going to be able to write all the stories I wanted to. With new determination, I set about writing a short novelette, something I could finish in a couple of weeks to prove to myself that I could write prose. It took me over six months. But the important part was that I finished it. Unfortunately, the reason it took so long was same problem I’d always had with prose. Every time I wrote a bad sentence, I couldn’t move on until I’d gotten it just right.

I’m not sure exactly when the second change struck — the epiphany that would finally break me free of my obsessive perfectionism, but I think it was not long after I wrapped up work on my first novelette and started on my second. I was working on some of the illustrations to feel productive during one of those times I’d ground to a halt over a bad paragraph, when suddenly, I realised how foolish I’d been.

Drawing is easy for me. I don’t need to enter a flow state for it because I’ve been doing it for so long. It’s just a task to be completed, and I can draw just as well when I’m not feeling it as when I am. By now I’m so familiar with my own capabilities and limitations that my art is going to look mostly how I expect it to. It wasn’t always that way, of course. When I was younger, there were mountains of discarded sketchbook sheets, crumpled and torn out of frustration because I couldn’t figure out how to get the picture in my head onto the paper. Every wrong line would be viciously erased, every splotchy shadow criss-crossed with dozens of layers of pencil as I futilely attempted to fix a mistake by adding more to it.

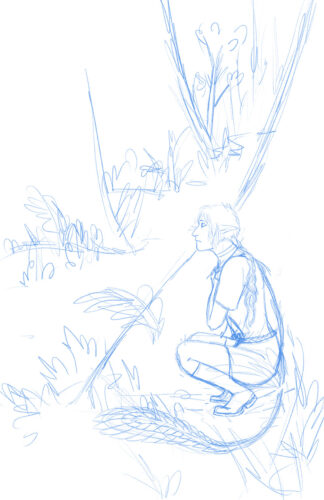

Eventually, over many years and many hundreds of attempts, I learned how to translate images onto paper. I knew how shadows fell, how light spilled over an object, how to layer colours and texture to add realism, how to make a subject look like they’re alive and moving, as if they could spring right off the page. I also knew that if one part came out wonky, I could just fix it. My armature sketches were sloppy, vague, ugly. But I was unbothered, because I knew that skeleton was just the first step of many, and by the time it was finished, I would have a beautiful piece of art.

I looked down at my rough illustration. That sloppy sketch with crooked appendages that barely resembled the thing I knew it was going to become. The thing I knew I was perfectly capable of turning it into. And I thought Why is it this doesn’t bother me, but a poorly worded paragraph does? Retyping a paragraph is a lot faster and easier than fixing a drawing. So what was my hang up? Why did I expect instant perfection and a fully realised novel on the first pass? My draft was a rough sketch. It didn’t need to be good the first time, it just needed to be good eventually. And that flow state I kept waiting for? I didn’t wait until I was brimming with inspiration to draw, I just sat down and did it. I did it every day until it came naturally.

Well, duh, you may be thinking. How could I miss something so simple? How could I master one art form and take so long to realise it applied to another? I blame my parents. They read me 19th century classics as a small child and it turned me into a literary snob. As a discerning reader, I wouldn’t be happy with my writing until it met my own sky-high expectations of what made a good book.

Tongue-in-cheek jokes (that are uncomfortably true) aside, it was tunnel-vision, and nothing less. I had to accept my amateurish writing and recognise that it would take time before I was capable of turning my sloppy word sketches into a finished prose painting. And just like with drawing, the more I forced myself to simply sit down and do it, the more I would know what the right words were, just as I knew what brushstrokes to make.

If I didn’t know how to draw, if I didn’t have the comparison of a rough sketch, I wonder how much longer it would have taken me to have this realisation. Since then, I’ve noticed how much easier it is for me to simply sit down and type words, even if they’re cringe-worthy. But now I know that’s okay, because I’ll just paint over that skeleton later.