NaNo (National Novel Writing Month) just ended, and I came away with a great deal more knowledge about my process than I started with. Now, I should note that traditional NaNo, that is, writing 50,000 words in 30 days, is far beyond my reach. I simply cannot write that much, that fast, without ruining my health. Instead, I set a much more modest goal of 20,000 words for the month of November, which I just barely met thanks to a cavalcade of setbacks midway through the month. The 20K I finished this month in addition to the 15K I put to paper in October was still enough to see just how differently this book is progressing compared to the light novel I wrote last Spring.

The light novel came to be in a somewhat roundabout way. I won’t go into too much detail since it’s still technically in limbo right now, but it started out as a short, 10 page comic script that got expanded into a 50 page comic script which, after several emails and zoom meetings, became a light novel. Having to expand the story (for a second time!) to fill the pages of a novel was a challenge, however I already had a solid outline to work from: that 50 page comic script.

Writing is hard. Every single writer says this. It’s a very different challenge from making a comic. Drawing a comic takes a lot more time and energy to cover the same narrative ground a novel does, but it has more leeway when it comes to the writing. Character expressions, body language, and visual decisions can do a lot of the heavy lifting, and make awkward or unrealistic dialogue less noticeable. Writing prose is faster and more flexible, but requires much more precision. With art, I can zone out and let my muscle memory do the work. With writing, I need to stay laser-focused the entire time. I could easily draw for hours and hours on end. I absolutely cannot write for more than one or two hours a day. The entire writing process is about solving one tricky problem after another. How do I bring this conversation to where I need it while making it sound natural? How do I bridge these two scenes? How do I write action without making it cartoonish? How do I pace the exposition scenes so it doesn’t come across as a boring info-dump? Is this sentence grammatically correct? Is this even a word? Oh, God, do I even know my native language or have I been speaking gibberish my whole life? Oddly, none of these were problems when I wrote comic scripts — those flow out of me with comparable ease — so translating a comic script into prose took a lot of the stress out of the process. I had to change quite a few things, of course, but there was always this overwhelming sense of relief when I finished a new scene created just for the novel and moved on to a scene that was in the script. I didn’t have to think as hard, I just needed to copy over the dialogue and change the stage directions into descriptions and then add some more flavour and detail. Thanks to using my script as a base, I was able to draft the book in far less time than any of my previous, shorter, books.

This taught me that I am not a planster (a portmanteau of planner and panster for the uninitiated; i.e. those who plan out the broad strokes of a story but make up the rest up as they go). So, I reasoned, what I needed to do for my next novel was plan everything out carefully.

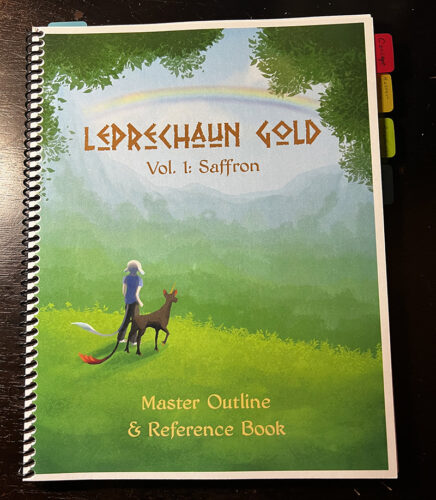

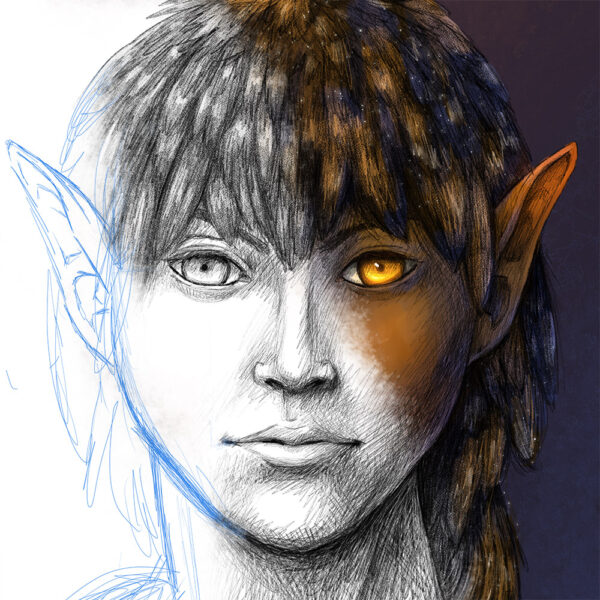

And I did. I spent a month writing a detailed outline for the first book of my Leprechaun Gold series. I spent several more months up to my eyeballs in research. I compiled everything into a reference notebook. I was damn fucking ready to knock out this manuscript. So I started drafting, knuckles cracking and filled with fierce determination.

And then… I struggled. I struggled hard. Over the past two months, I wrote 35K words for this book. So far, the total word count for the book is 25K. I lost 10K somewhere, in all the teeth-gnashing rewrites as every day I had to go back and delete half of what I’d written the day before. I kept straying from my outline, or forgetting how I originally want to lead the story from one bullet-point to the next, and coming up with the most ridiculous, convoluted ways to move the story to the next scene.

Clearly, something here isn’t working.

I’m going to continue on with this outline until the book is finished, to see how much more I learn about my process from this. Will I keep struggling and losing almost half of my word count to course-corrections? Or will things smooth out after I power through the early chapters? How much rewriting will happen when I edit later on?

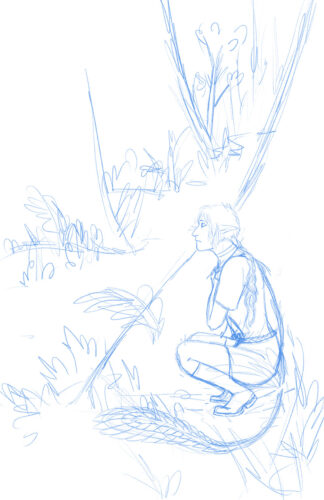

The biggest lesson I learned is that scripting comics comes naturally to me, and writing from those scripts is much easier than following a traditional outline. When I go to outline my next book, I want to try writing the story as a comic script, and then writing my first draft from it. Like painting over a rough sketch.

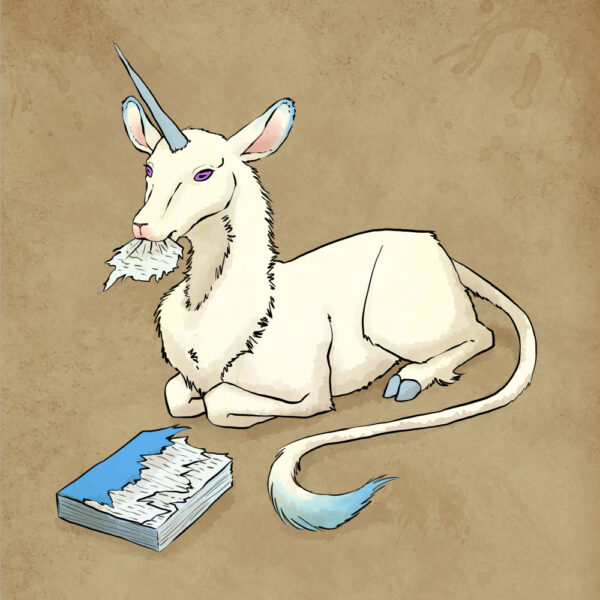

While it’s been frustrating, this year’s efforts have been an invaluable insight into how my brain handles outlines. As I put down tens of thousands of words that get deleted shortly after, I remind myself of the mountains of wonky sketches mouldering in the dark corners of my closet that were the necessary collateral before I could draw well on command. Right now, every prose project is a wonky sketch that I learn something important from. And if I keep at it, maybe someday I’ll be able to write as effortlessly as I draw.