3.4K words – 17 minute read

July 13th, 735: Evening

I have finally gone mad. It was a short trip, to be sure, but this time I’ve really lost it.

Only four hours ago, my life was achingly normal, and I wouldn’t believe what I’m about to write myself if it weren’t for the two creatures curled up asleep only a few feet away from me.

The setting sun was hot on our backs earlier as my father, my brother, and I tended the barley fields as usual. I was exhausted as I bent and yanked at the endless yarrow leaves infesting the field. It’s dull, tedious work that allows my mind too much freedom to dwell on my grief.

Finishing the day’s tasks would have been little relief, however. I’d only return to my empty cottage, bereft of Camden’s quiet presence and the laughter of the children we were never able to have before Azrael, the dark angel of death, spirited the other half of my soul somewhere far beyond my reach. There I would sit as I did every evening, the sweat drying on my skin, and the emptiness hollowing me out until sleep brought me fleeting respite.

As I wrestled with yet another yarrow’s stubborn roots, I didn’t know which was worse, the exhausting tedium of right then or the quiet emptiness that would come later.

Suddenly, the sky darkened. A huge shadow was passing over us. I looked up, saw a glimpse of black scales, and then everything happened so fast. There was shouting and running. The dog barked ferociously. An unearthly screech made my ears ring, and the thump-thump of enormous wings beating filled the air. A spear was pressed into my hand, and I heard the sharp hiss of arrows being loosed. Before I knew what was happening, it was over, and a huge beast lay bleeding out in the soil at our feet.

Father and Brian talked of scouts and danger and war. About how wyverns came from the Veslian Empire, a vast and powerful war machine from far across the sea. They said more, but I barely paid attention. All I noticed was the creature dying on the ground.

She was a frightening sight: thick muscles covered in black scales, a narrow snout filled with needle teeth, and long, curving horns. She had a stork-like body, a thick lizard’s tail tipped with three sharp, venomous barbs, and leathery, bat-like wings. I had heard of wyverns before, but I never imagined they were so terrifying. Nor so magnificent. My chest squeezed painfully to see such a stunning creature slaughtered for doing nothing more than fly overhead. I know Father and Brian meant well — they saw what they thought was a threat and reacted accordingly — but I still felt heartsick and queasy at the result.

And then my nausea doubled when I noticed the wyvern’s belly. It was round and distended. She was pregnant and looked nearly due.

A tiny green shape was moving behind the creature. I shoved between my father and brother, exclaiming, and crouched down for a better look. It was also covered in scales, but this was no wyvern. A dragon! I had half-believed them to be myths, but here was one right in front of me. It must have hatched not long ago; it was so small.

I reached out my hand to touch it, but Father yanked me away. He said dragons are powerfully magic and would curse us if we laid a hand on them. I thought that was silly superstition, but I didn’t argue with him, especially as it meant he wouldn’t risk harming the dragon himself. Then he and Brian walked away, leaving the wyvern to die of her wounds and the baby dragon to die of exposure whilst I remained standing there on the bloodied soil with the dragon’s desperate mewling ringing in my ears.

It was at that moment I discovered wyverns are not mere beasts. The dying mother opened her jaws and spoke, her voice rasping like a wet cloth drug over gravel. There was no malice or anger in her words. She only begged me. Begged me to save her unborn before it died with her.

The words slammed into me, leaving me breathless. I don’t know why they affected me so deeply, but it was, perhaps, the utter unfairness and cruelness of circumstance. My husband had perished before he had been able to give me the children I craved, whereas she had a child she would never live to see. I admit, for a brief moment, I hated my father with a vitriol I had never thought myself capable of. It was that anger that motivated me to do what I did next.

I agreed.

I pulled out the knife I always keep in my skirts and set about the gruesome work of cutting her unborn young from her belly.

Now I am back in my cottage, my clothes still stained with her blood, and two baby dragons sleeping in the cat’s bed.

I think I will have to leave off here. The full reality of what I have done is just starting to sink in, and my hand is trembling so fiercely I can scarcely hold my quill.

July 13th, 735: Nightfall

I’ve washed and am feeling a little steadier. Only a little. I fed the baby dragon some smoked ham I had from last winter, but the newborn wyvern refuses everything I offer him. He will have to wait till morning for me to figure out what he eats. The sun has sunk below the mountains, and there is no daylight left to venture out and search.

Tip-Toe hasn’t returned home for the night, but that isn’t unusual for her. I’m sure she’ll be yowling to be let in before the sun is up. I hope she will not make a fuss when she sees she has two new housemates.

The dragons are fast asleep. My rushlight has burnt so low I have to strain to see what I am writing. I need sleep too, but my thoughts keep buzzing around my skull like angry bees. How will I care for two creatures when I know nothing about them? Are they really helpless babies, or are they as dangerous as Father thinks they are? What if I can’t find out what the wyvern eats — will he starve? How am I going to hide this from my family? Should I tell them? With how stubborn and narrow-minded Father is, would it even be possible to convince him this was the right thing to do?

Was this the right thing to do?

July 14th, 735: Morning

As I predicted last night, Tip-Toe was scratching at the door as soon as dawn broke and wailing loud enough to wake the dead. I let her in, and she puffed up the moment she saw her bed occupied. She immediately ran back out, and I presume she is now sulking somewhere.

The baby dragon demolished the bacon I offered in only a few bites, then raided a sack of apples. I found it surprising dragons are omnivorous; you certainly wouldn’t know by looking at them. Once again, I offered the wyvern a variety of different foods, but he still refuses everything I have. He’s been crying out in hunger all morning, but his voice is getting weak. I must find him something, and quickly.

July 14th, 735: Afternoon

I don’t usually believe in happenstance, but whether it was fate or pure dumb luck, Tip-Toe came back a few hours ago with a fish in her mouth. She’s seldom able to catch them by herself, so with her head held high, she swaggered through the door to show me her still-wriggling trophy. As soon as the little wyvern smelt it, his whole demeanour transformed. He began squirming and whining and trying to crawl out of Tip-Toe’s bed to where she was crouched on the hearth, playing with her catch.

With only minimal guilt, I took it from her and put it in front of the little wyvern. He swallowed it down in a single gulp. I ran the entire way to the village square to buy some more fish from old Angus’ morning catch.

On the way, I had to pass by the mother wyvern’s body. Some of the village lads were digging a pit to bury it. I felt sick when I saw her horns had been sawed off and set aside as some sort of grisly trophy. I hurried by quickly, thankful they thought my look of disgust was for the body and not for them.

I’m now back home, covered in scales and blood from dressing the fish, but the wyvern is finally full and happy. Tip-Toe is still giving me dirty looks, but she’ll recover.

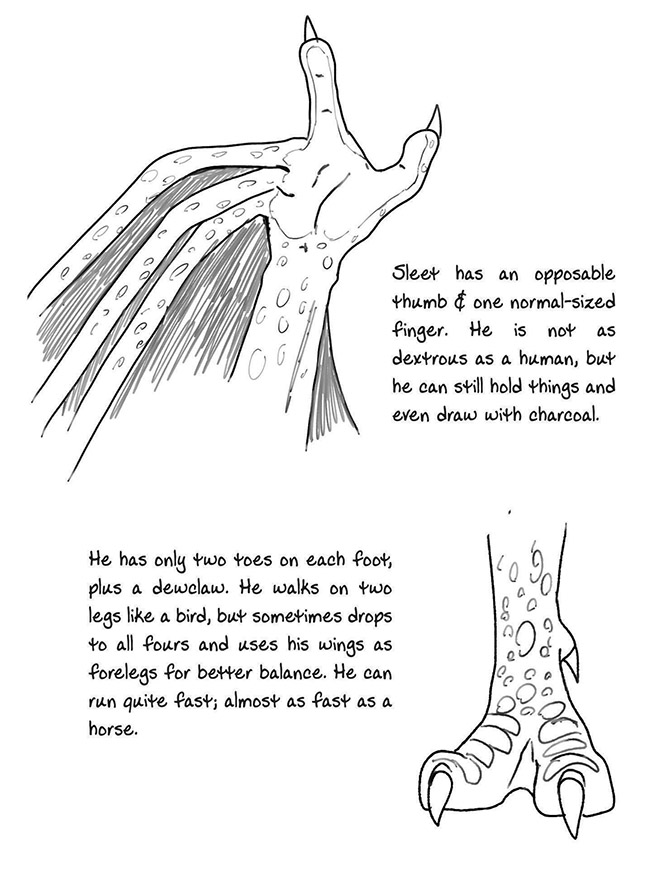

For the first time, I can really sit down to study these unusual creatures. The wyvern looks like a smaller, chubbier version of his mother, except that his scales are a translucent white rather than black. I have seen colourless creatures like him before, and know the phenomenon is called albinism. His huge wings double as arms: three fingers of his hand are elongated and webbed, while his thumb and first finger are normal sized. I know that thumb is opposable, since he used it to grip the fish I fed him. Like his mother, he has no visible pupils in his large, pink eyes, which is more than a little unsettling. His tail is tipped with the three, infamous barbs of the wyvern, used to inject a paralysing venom that can be deadly in all but the smallest doses. They are still soft and harmless, but I will definitely be trimming them down once they harden.

Unlike the wyvern, the dragon has six limbs: four legs and two violet wings that fold along his back. He is all around stubbier and thicker, with none of the wyvern’s lithe sleekness. His bluish-green scales are pebbly and he has floppy, fin-shaped ears that are so ludicrously over-sized that he keeps accidentally tripping on their drooping tips. His claws and horns are a golden colour, as are the blades at the end of his tail. I may have to file down the points of those, too.

As I’m writing this, the dragon has crawled into my lap, making the cutest purring growl as he curls up to nap. It’s only been a day, and I already love these creatures more than I ever thought I could.

I know I did the right thing. I’m sure of it.

July 16th, 735

I feel terrible. Today I lied to my family for the first time in my life.

Father and Brian came visiting this afternoon — Buckwheat, our old family sheepdog, tagging along — to see how I was doing, worried they hadn’t seen me since they slew the mother wyvern. They suspected I may have fallen ill from the shock. As if I’m that fragile!

I had been playing with my new charges when they came knocking at my door. I panicked and threw them into a cupboard. I had a few seconds to beg them to keep quiet — though I doubt they understood me — before I closed and latched the door. They wouldn’t be in any danger of suffocating, but I didn’t fool myself for a moment into thinking they would stay silent.

When I opened the door, I was flushed, sweating, and jumpy, which confirmed to Father and Brian that I was as unwell as they’d feared. I was immediately bombarded with well-meaning advice while I tried to think of a way to get them away from the house.

‘Why don’t we talk out in the garden?’, I told them, fanning myself with one hand. ‘It’s so hot and stuffy here in the house.’

That wasn’t a lie — it was mid-July, after all — so they had no trouble letting me usher them into my herb garden where I sat them down on some rough-hewn stone slabs that served as benches.

‘How have ye been, Daughter?’ my father asked as he took out his old hand-carved pipe and a small box of tobacco. ‘I’m sure the other day must have given ye a terrible fright.’

‘I am a little shaken’, I said, finding it easier to tell a half-truth than a full lie.

‘Anyone would be!’ Father declared, waving his pipe in the air. ‘I nearly lost five years of me life when I saw the beast fly overhead!’

Brian, pensively stroking Buckwheat’s grizzled head, said quietly: ‘I’ve heard tell of those beasts.’

‘Have ye now? When was this?’ said Father, his now-lit pipe between his teeth.

‘Once’, said Brian, ‘when you and Harley and I went down to Port Osstero to sell wools. It was the summer we had those huge swarms of deerflies, remember?

‘Well, while you were haggling prices in the market, I met a seadog at the inn, who said he was from Yrren. He didn’t talk much at first, but after a few mugs of ale, he starts telling everyone how he became a sailor. Said his village back home got raided by wyverns. They carried lit brands in their talons and burnt down all the buildings. Slaughtered men, women, and children alike. They were like demons, he told us, savage, bloodthirsty monsters who only cared about killin’, and he barely escaped with his life. He even showed me his scar. Huge, gnarly thing, went from his chin down to his hip. Said a wyvern did that with just one kick of its talons.

‘After that, he had nothin’ left. No home, no family, no trade. Went to the nearest port and signed himself up on the next ship, said he never wanted to go back nor see a wyvern again in his life.’

‘Aye’, said Father, chewing at his pipe, ‘I’ve heard countless similar tales all me life. Those things, they can’t be reasoned with, and ye can’t beg them for mercy because they got none. I’m only thankful there was just one this time, but mark me, I’ve been watchin’ the skies like a hawk to see if anymore start flyin’ overhead. Told the whole village to keep a lookout, too.

‘But don’ worry daughter’, he said when he saw how pale I’d gotten, ‘we’re all keepin’ close watch, so ye’ll be safe. Gleann Beithe may be a small village, but we won’ let any attacks like that happen here!’ He thumped his fist on his stone seat for emphasis.

‘Of course’, I said, feeling rattled.

The mother wyvern had been perfectly capable of reason. She had plenty of mercy, too, seeing as how she’d begged it for her young. Her only display of ‘savagery’ had been to protect them.

Father and Brian seemed ready to settle in and make an afternoon of their visit, but I managed to convince them I was fine, only that I needed some rest. When they finally gathered themselves up and headed home, I breathed a sigh of relief.

Buckwheat was harder to shake. The old sheepdog stayed behind, insistent on sticking to me. I don’t know if he could sense my nervousness and wanted to comfort me, or if he was hungry and I still smelt of fish.

I headed back inside, hoping the cupboard hadn’t gotten too hot. ‘You won’t tell anyone my secret, will you?’ I said to Buckwheat, my hand on the cupboard door. The dragons inside were scratching and whining.

Buckwheat tensed, no doubt alarmed by the unfamiliar sounds and smells.

When I opened the door, the babies shot out. The little dragon reared up on his hind legs, letting out a fierce little roar that sounded like a cross between a puppy’s bark and a cat’s yowl.

Buckwheat barked furiously, shoving me away from the perceived threat. The dragon growled back with equal ferocity. I feared they might try and hurt each other, so I threw my arms around the sheepdog’s middle and pulled him away.

It took a while, but I managed to calm down both dog and dragon. Buckwheat still seemed wary until the little wyvern lolloped over and begged him to play. After a thorough sniffing, the old sheepdog must have decided he was all right because his jaws hung open in a big smile. The two started gambolling about, and it wasn’t long until the dragon joined in.

The animals played with each other all afternoon and into the evening. They constantly barrelled into me and got underfoot as I picked the ripe courgettes from my vegetable patch, and more than once the contents of my basket were scattered everywhere.

I didn’t mind.

December 23rd, 735

I can’t believe it’s already been five months since I became the guardian — no, the mother — of a dragon and a wyvern. I could have adopted some more cats or kept a kennel of dogs, but no! That wasn’t enough of a challenge for me, apparently. I had to go and take in two of the most dangerous creatures in the world.

Although, it’s challenging to think of them as dangerous when they cuddle up to me at night, play with Buckwheat, or get their heads stuck in the apple basket.

That last one is only Arra.

Oh, I don’t think I’ve mentioned before that I gave them names! I’ve been so busy caring for them over the past few months that I’ve neglected my journal terribly. In any case, I named the little wyvern Sleet for his colouration; as he’s grown, his scales have hardened and taken on a silvery sheen that reminds me of sleet sheeting down.

When I first took him home, he was so little he couldn’t walk upright and used his wings as forelegs. Since they are shorter than his back end, it gave him an awkward, wobbly gait, which made me laugh on more than a few occasions. He’s at least five times bigger now, and not only can he stand on his hind-legs just fine, he can also run alarmingly fast. Sometimes I worry he will run too far from the house and be spotted. He’s starting to speak, though mostly he only says ‘fish’ and ‘want’. I tried to teach him to say his own name, but somehow he manages to pronounce ‘Sleet’ in a way that sounds almost exactly like ‘shite’.

The dragon has grown quite a lot as well; he’s nearly as tall as my knees. His ears are not quite so large for his body anymore and he has started sprouting a golden mane that runs from the top of his head to halfway down his tail. I don’t know if he is capable of speaking like Sleet, but when he’s being affectionate, he makes a little growling trill that sounds like ‘arra’. It’s so adorable, and he does it so often that I started calling him that. I should probably give him a proper name, but I think it may have stuck.

I never realised that taking care of two dragons would be such an enormous endeavour. I suppose I had thought of them as only a little above animals, and that they would take as much care as a new calf. Now I know they are in fact children who are as intelligent and complex as humans. Sleet is especially sharp, and more than once I’ve been the victim of one of his pranks. He once stuffed my flute full of barley flour, if you can believe it! I didn’t realise until I tried to play it. I wanted to scold him, but I was laughing too hard.

They have brought me so much joy — a joy I wish more than anything I could share with my family, but I have seen how much hatred my father harbours towards these creatures. Once or twice as he was regaling the tale of his ‘battle’ with the mother wyvern in the tavern at night, I tried to drop a few subtle hints that she was only trying to protect her young. Each time I was met with not only scepticism but outright hostility. The mother’s horns are mounted on the wall, looming over me, a constant reminder of the fellow patrons’ prejudices. I don’t think anyone in Gleann Beithe is anywhere near ready to know about Sleet or Arra.